Welcome to Rolling History, a small project exploring the digital presentation of later medieval English history rolls!

Codices, scrolls and rolls

The standard way to transmit text in medieval England was a set of pages between two covers. This is called a ‘codex’. The codex remains the standard shape for physical books today.

The codex wasn’t always the dominant container for large amounts of text in Europe: until late antiquity, so up to around 1600–1700 years ago, texts were more often stored and transmitted in scrolls and rolls.

To move through a scroll you must continuously roll and unroll it at both ends. If you want to compare something at the start of a scroll to something at the end, you have to move through the whole scroll on the way. In a codex it’s quicker and easier to flip between different parts of the object. This advantage may be one reason why codices replaced scrolls for most purposes during the Middle Ages.

However, the physical form of the roll continued to be used by medieval people, particularly for record-keeping. In scrolls from the classical period the writing is normally arranged laterally along the object’s length in a series of columns. Medieval rolls, on the other hand, were normally copied and read vertically, with the writing running down the length of the roll in a single column.

One cluster of surviving fifteenth-century rolls, including the one pictured above, all contain a history of the world organised as a long genealogical diagram. The English text on these rolls is descended from Peter of Poitier’s early thirteenth-century Latin Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi, probably via the mid-fifteenth-century Latin genealogical chronicle of Roger Alban.

One reason for the use of this format might have been the association between the physical shape of the roll and the activity of record-keeping. These particular rolls begin with Adam and Eve, but move from Biblical and Roman history to the history of the English monarchy. They finish with Edward IV, who took the throne in one of the series of conflicts which are popularly known today as the Wars of the Roses. Perhaps, then, the format was also attractive in this case because it forced continuity on the material: one continuous diagram on a continuous object could smooth over complex and violent dynastic history.

Digital rolls

Since the arrival of computer screens, a lot of reading has shifted back to scrolling—particularly, scrolling in the medieval manner, vertically. However, most of our infrastructure for digitising medieval manuscripts and displaying digital facsimiles of them online assumes that medieval manuscripts are codices.

As a result medieval manuscript rolls have often been displayed online in a series of page-shaped slices. Users are expected to ‘turn’ between these as they would in a digitised codex facsimile.

It’s now possible to take photographs of a medieval roll, stitch them together into a single digital object, and offer that to users as a single scrollable object, replicating more closely the medieval reading experience. One goal of this project was to see how well the IIIF authoring tools being developed by the Bodleian cope with this kind of long, unwieldy digital object.

Roll-codices

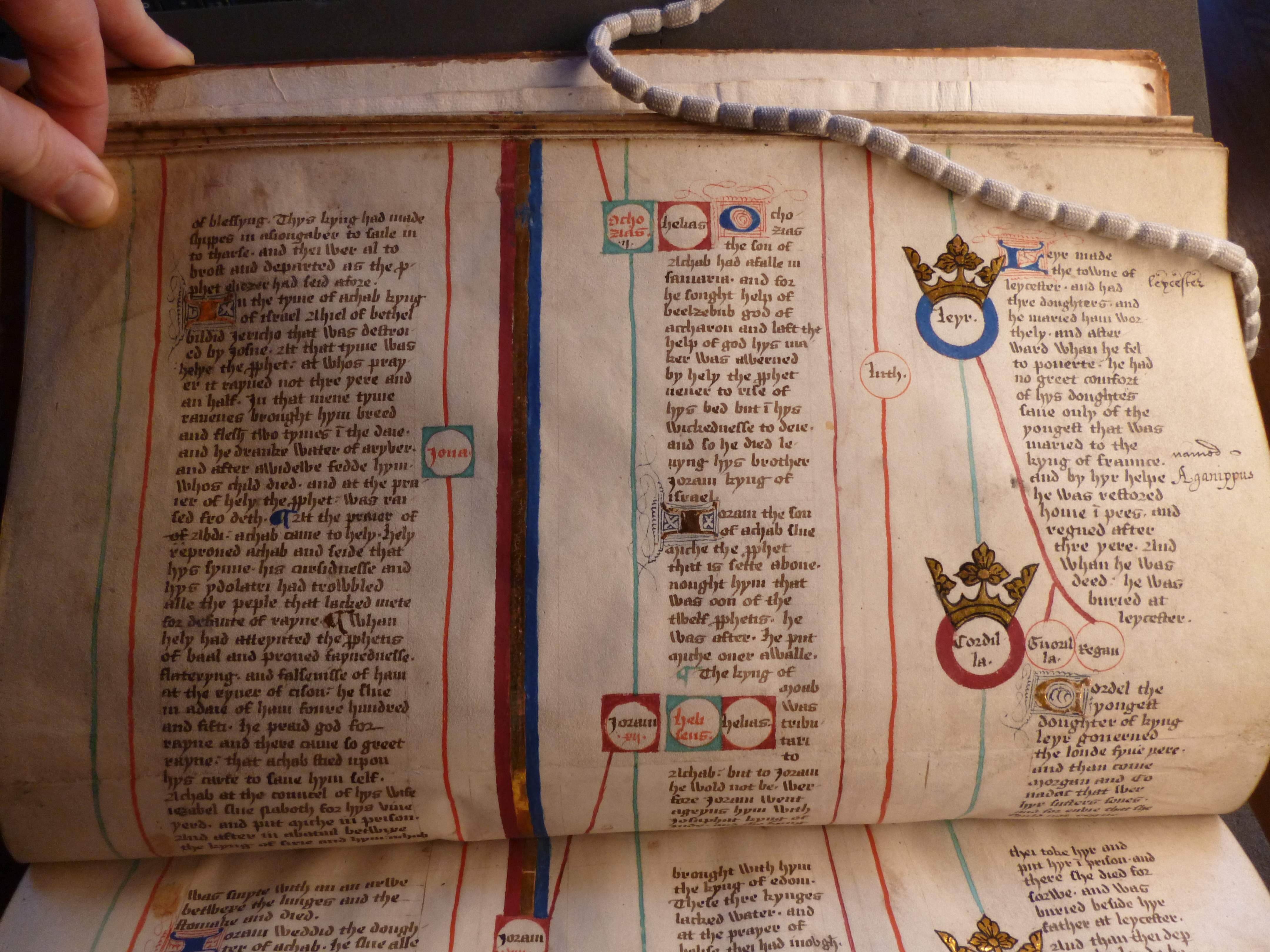

The distinction between roll and codex is blurred by the form of the roll-codex. This is text laid out vertically on a single physical roll with gaps at regular intervals. The roll is then folded at the gaps into a series of leaves and bound in a normal binding as a codex.

The resulting object is a codex which has to be read ‘sideways’. We can tell that roll-codices were designed to be roll-codices, and are not simply rolls which have been forced into the shape of a codex: the gaps and guides which the scribes involved carefully ruled for themselves show how carefully planned these objects were. In the picture above you can see the gap left at the top of the page so that the fold in the roll would not interrupt any writing.

This was a popular format for the English genealogical history discussed above, though we have no settled understanding of the motivation behind making roll-codices containing this text. Perhaps roll-codices were a concession to the codex-attuned reading habits of the period, an admission that while rolls were physically impressive, the effort involved in rolling back and forth within them to consult different parts could be too much.

Digital roll-codices

A roll-codex can be digitised just like a codex. But, again in pursuit of use of the digital to open up new ways of reading, also we can also stitch together images of a roll-codex to make a digital roll. That is to say, we can unroll the roll-codex, producing an object like this:

This is an impossible way of reading the physical object: stitching together images into one larger entity turns photographs of simple rolls into something closer to the original object, but it takes photographs of a roll-codex further away from the original object. As with the digital rolls discussed above, seeking out an ‘impossible’ way of reading like this might give us new insights.

It might also be possible to place a digital roll and an ‘unrolled’ digital roll-codex containing the same text alongside each other in some annotated form, enabling close comparisons between the two kinds of objects which were previously impossible.

A note on hands and gloves

Bare hands feature in a few of the photographs here. Occasionally people ask why we don’t use gloves when handling medieval manuscripts. In fact, wearing gloves to handle a manuscript usually creates more risks than using clean dry hands. For more on this debate see Margit J. Smith, ‘White Gloves, Required—Or Not?’, in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 15: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Seminar Held at the University of Copenhagen 2nd–4th April 2014, ed. by M. J. Driscoll (Copenhagen, 2016), 37–52.

Stitched roll photographed by the Bodleian Library; all other photographs by Daniel Sawyer, reusable under CC-BY licence.